Chromium Ozone-GBM explained

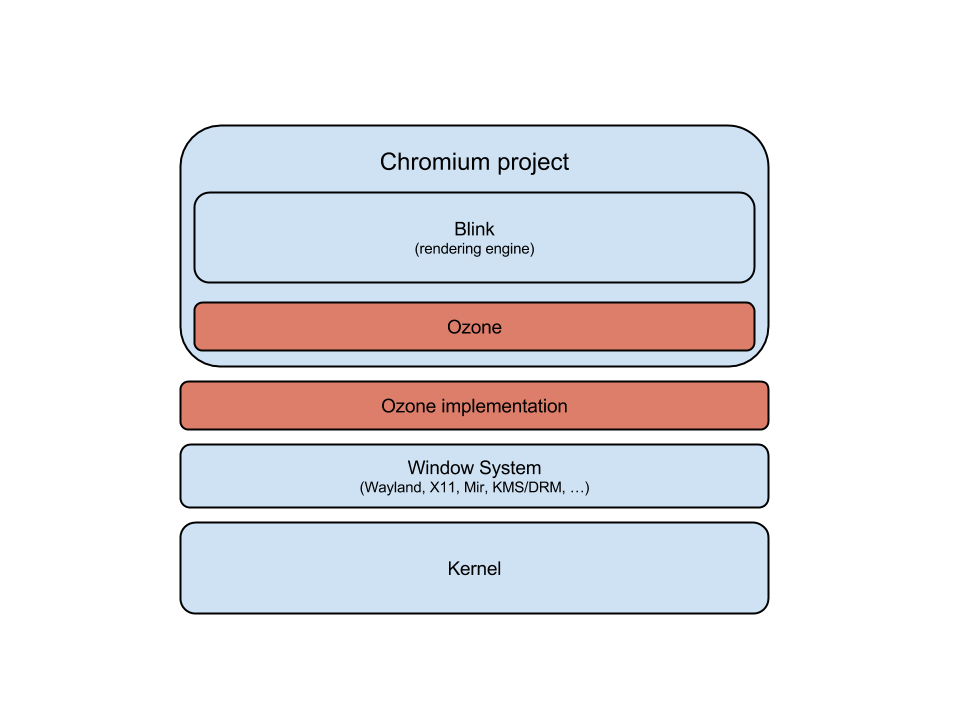

About a year ago Ozone platform abstraction layer started to take its shape in Chromium and we were excited how easily we could support Wayland platform using it. Everything went great and we helped a few Chromium targets like Crosswalk to debut in the Tizen ecosystem for example. More recently, different Ozone platforms have been implemented and only now it’s becoming evident the significance of Ozone for Chromium Linux, generally speaking.

In this post I will focus in the Ozone-GBM platform, which is the platform that gives support for hardware-accelerated graphics and input support in Linux, without relying on any traditional windowing system like X11, Wayland etc. I hope that after reading this document besides a better knowledge on Ozone-GBM itself, the reader will also have an overall idea how Linux graphics and Chromium architecture function together.

LINUX, OPENGL, EGL, GBM AND MESA

When building modern and beautiful UIs, the GPU is the hardware engine responsible to produce compelling graphics representation of their images and output them to the screen. On the software side, OpenGL is the well-established API for rendering graphics using a GPU and Mesa is the Linux open-source library implementing it.

In practice, OpenGL (and its subsets OpenGL ES 1, OpenGL ES 2, etc) usually comes accompanied with a few other APIs to handle platform and system details, one of them being EGL. EGL is the generic interface for dealing with different windowing systems operations like surfaces binding, rendering synchronization, among others. Besides EGL, there’s also the KMS/DRM kernel subsystem together with its userspace library used for performing display mode setting and frame-buffer related operations. But when we are mixing together these three major components – GL, EGL and KMS/DRM – there is a missing component for performing memory allocation. Previously this was solved by hardware specific drivers on X window system (X11), but if we wanted the user application directly allocate memory then it would be a real problem, which would be solved only later by Mesa GBM.

Mesa GBM (Generic Buffer Manager) basically provides a EGL native window type (just like Wayland and X11), so one could obtain a real EGL surface and create render target buffers. With that then, GL can be used to render into these buffers, which will be shown to the display by queuing a page flip via KMS/DRM API.

It’s important to note that the only public implementation of GBM is the one based on KMS/DRM, therefore although it’s a “generic” library for accelerated buffers so far we have seen only one out there (!). Besides, by now you may have noted that Ozone-GBM is probably not the most suggestive name about what is in fact this platform.

CHROMIUM UI FRAMEWORK, AURA AND VIEWS

Jumping now to Chromium, in the graphics side of the things we have Aura/Views UI framework. Aura is the acceleration graphics system in Chromium. Views is the widget toolkit based on Aura, so one could build buttons, dialogs etc easily with Views but not with Aura. Aura has a very simple concept of window which receives messages for input event handling, painting, and other low level tasks. On the other hand, Views widgets (views::NativeWidget) are responsible for translating platform-specific notifications into cross platform events.

For example in Chrome Browser, what we see in our desktop screen including the Web contents (“renderer”), main tool bar, window frame, search bar (“omnibox”) and etc are constructed basically from a bunch of Views, each backed up by a Aura window, which in turn are hosted within one single Aura root window (aura::WindowTreeHost, one per display actually).

aura::WindowTreeHost bridges between Aura windows and the native root window, i.e. where the real platform-specific code lives. Depending on the platform there will be a root window that wraps one X11 window (aura::WindowTreeHostX11) or one that wraps an entire and robust graphics system (ui::DriWindow), in case of Ozone-GBM.

Before we move on, it’s important to explain a few concepts used in Chromium. Compositing is the phase of rendering that combines layer’s textures into a final screen image. Drawing is the compositor combining layers into the final screen image; while painting is the population of layers’ backings (bitmaps with software rasterization; textures in hardware rasterization).

That being said, the root window inherits the compositor object (ui::Compositor), so whenever a draw is triggered in the root window aura::WindowTreeHost, Chromium compositor walks through the child windows, painting the invalidated regions of them and making sure the final result will be presented on the screen (ScheduleDraw()).

FULLSCREEN VS. DESKTOP TARGETS

There’s a variety of targets that Chromium lets us build such as Chrome Browser, ChromeOS, Chromecast, Crosswalk runtime and many others. We basically can split these targets in two classes, depending how the user-interface behaves on each target:

-

the first class, where a Chromium target controls the entire display, e.g. ChromeOS or Chromecast

-

second class, the ones that are only part of a multi-window desktop UI, e.g. Chrome Browser in a desktop system

In the second class of targets, aura::WindowTreeHost (more recently actually split into ui::PlatformWindow) needs to implement all the interactions with the windowing system (resize, maximize, close, etc) and controls the dispatch of the native input events to high-level delegated Chromium interfaces. This is rather complex mechanism and although it’s difficult to get it correctly this type of support was the first that existed in Linux Aura infrastructure (“Aura-X11”). Interestingly, this same support was being used so far for the first class of targets. Note though that the underlying windowing system for these fullscreen targets could be very simple, because the platform window corresponds practically to a physical display (“why maximize or resize a root window? It doesn’t make sense”).

In other words, fullscreen Chromium targets require minimal interaction with the windowing system and the few other tasks that were being carried through it, like input devices, display management or media support, one would argue that are not tasks inherently of the window system.

OZONE-GBM

Finally, and now speaking with authority, we can define it: Ozone-GBM is the native fullscreen-only platform that delegates the composition tasks of Aura root window to a new Chromium platform window based on KMS/DRM, ui::DriWindow. In ui::DriWindow, EGL is used for drawing and OpenGL ES 2.0 for rendering. Also, display synchronization (“page flip”), display configurations are handled by this platform. A smart logic to use hardware display planes (“overlay”) is also implemented in there.

Besides, Ozone-GBM has an internal implementation of the Linux evdev subsystem (ui::EventFactoryEvdev), so events emitted by input devices can be processed and handled accordingly to the needs of Chromium targets – touchscreen devices, touchpads, keyboards and mice are somewhat supported by Ozone’s evdev driver.

SUMMARY

-

Ozone is a platform abstraction layer beneath the Aura window system that is used for low level input and graphics.

-

In Linux graphics, Mesa GBM provides the ability for user application directly allocate accelerated graphics buffers.

-

Fullscreen Chromium targets such as ChromeOS, Chromecast among others require minimal interaction with the native windowing system.

-

Ozone-GBM is the native fullscreen-only platform that delegates the composition tasks of the root window to a new platform window based on KMS/DRM. It uses EGL/GLES2 for accelerated rendering. Besides, Ozone-GBM has an internal implementation of the Linux evdev subsystem.

-

Fullscreen Chromium targets can use Ozone-GBM to remove unnecessary dependency on full-fledged window systems like X11, Wayland, DirectFB, etc.

Out of the scope of this article but worth to mention, is Ozone-DRI implementation. It uses KMS/DRM infrastructure as well but scanout content is displayed via software rendering, using double-buffered Skia surfaces. This implementation could be particularly useful for budget devices, for example those that don’t have GPU at all. (Besides, Ozone-DRI also has a quite bad nomenclature because “DRI” refers to X11 direct rendering, even though X11 is not used at all there).